Administrative Transparency

A letter submitted to the office of the Academic Dean asking for student representation on academic and student life councils.

Student Goals and Intentions

In the mid to late twentieth century, Universities were changing in nature as the result of desires for changes in administrations and student representation amongst student populations. As historian Christopher Loss claims there were major differences between 'new' universities and the 'old,' one of these differences being that "the new university was inclined to be more impersonal, more permissive, [and] less directly engaged in student supervision."[1] While these changes did slowly come into being during this time, it was for most universities the results of students demanding their rights to be treated so. Student activism affected the priorities in university admissions by calling on them to be more transparent and to be more of a working system to aid students than an overpowering governing system.

During the 1960s and 1970s, student activism increased as students began to demand more of their universities who were not meeting their standards of inclusivity in matters such as deciding course materials, and the extent to which students would be allowed to curate their own college experiences. For St. Edward's students in particular this meant becoming energized for issues that all supported one main goal: to have their opinions heard and considered in rules and regulations made by having a place on student governing councils.

As students found their understanding of the requirements of an ‘adequate’ education changing, so did their opinions on who could best represent those ideas. In the Student Activities Council’s 1968 proposal to the administration, students proceeded to ask that there be a student representative present on two of the most important administrative councils and at all their meetings.[2] These proposals served as one of the main forms in which students were active since it was just about the most effective way of reaching administration directly without being turned away. Since in numerous news pieces, the students had been seen as irresponsible or immature, this was their mature and more serious means of making demands heard.[3] By proposing that a student representative be present this also avoided the possibility that the administration might coddle or half-answer student questions and requests.

As students began to react to these requests, it brought about issues in defining student organizations by means of what their relationship was with the administration. Concern was expressed amongst students through remarks in the student paper about what the jobs of organizations such as the student government even were and how they were benefitting the general student population. Students became adamant about shifting their goals from student representation through student clubs, to student representation becoming a working factor with administration.[6] By putting themselves on an even playing field, at least in being aware of information that would affect student life, students felt they would earn that needed respect and responsibility they desired.

Actions Made Toward Progress

As student activism in other universities often proved, demanding large and sudden changes rarely resulted in the administrative reactions the students visualized. In their own sister school The University of Notre Dame, St. Edward's students watched president Theodore Hesburgh ridicule the student activists on their campus, threatening them with expulsion and city police intervention.[4] Due to incidents such as this, students at St. Edward's University worked towards minor ‘privileges’ hoping they would give them the leverage they needed to gain larger responsibilities and voices on campus. As expressed by the tone of numerous news pieces, the administration often times refrained from permitting these large responsibilities out of a lack of trust in their students to handle them.[3]

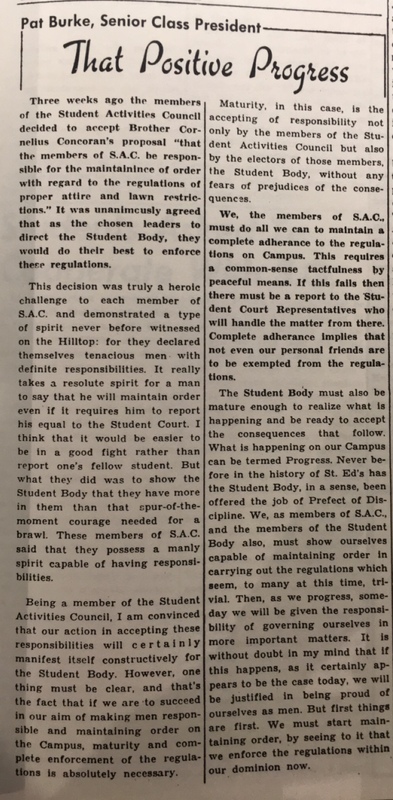

In the clipping of the student newspaper, The Hilltopper, titled "The Positive Progress" the message expressed was the extent to which and the reasons the administration was giving more power to students to curate their own quality of life on campus. The student body president wrote that the members of the Student Activities Council decided to give minimum responsibility to students to dress themselves properly without a uniform and creating respectful lawn privileges. At this time the student body had been granted extremely limited responsibility when it came to controlling the quality of their on-campus lives and the feeling expressed was that it may be due to administration not believing they were yet mature enough for such matters. As the student body president notes, this small step may seem fetal but was a start for them to eventually be responsible for bigger issues and gain rights they believed they should have.[5]

The Hilltopper became the main outlet through which students felt they could voice their opinions without being punished or ridiculed. The actions committed in the spirit of activism, such as students having to ask for trivial responsibilities in hope for large ones, led to changes in administrative priorities as they began to witness a change in students and their unwillingness to be entirely controlled without their own suggestions implemented.

This Positive Progress was a part of the small but upward-sloping steps that would demand the administration to listen and take actions that would treat the student body as a working part of the university rather than what fills it. While St. Edward's was not known as one of the main hot spots for activism in the form of walkouts and strikes as other universities were, the students of this university found and mastered the method that worked best with the institution they were working within. The success of these methods is seen in the way the university operates today as a system working for and with the students for an all-inclusive goal of obtaining higher education in its best form.