Pushing for Rights: Minority Activism

Across the Nation and At Home

During the '60s and '70s minority populations were fighting for rights and representation across the nation after the decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 that effectively overturned the separate but equal decision of Plessy v. Ferguson. One of those focuses centered on representation and equal treatment in higher education. The black civil rights movement pushed for both inclusivity within existing colleges and university programs as well as the establishment of Black or Afro-American Studies programs.

The Chicano community followed a similar path based on the black civil rights movement to establish Chicano studies programs, bilingual references, as well as Hispanic Serving Institutions.[1]

At St. Edward’s University the attitude toward minority groups wasn’t too far off from the rest of the country before the 1960s. Representation of any minority groups prior to the '60s is little to none in yearbooks. However it is important to note that St. Edward’s University was a private institution and was not obligated to comply, with state segregation laws prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1965, nor did it.

Overall student activism at St. Edward’s University followed the path of others in their community and throughout the nation and pushed for the modifications they desired on campus throughout the '60s and '70s, which led to an increase in representation of minority populations.

Black Representation at St. Edward's University

During the 1960s St. Edward’s University began to promote the inclusion of black students in the yearbook and welcomed them on campus more readily than other higher education campuses across the nation who were resisting their inclusion. The 1965 St. Edward’s University yearbook, The Tower, included a written piece stating awareness “that the University exists to deliver a Christian liberal education” and “the Student Council is jealous of its obligation...to contribute to this freeing process.” [2]

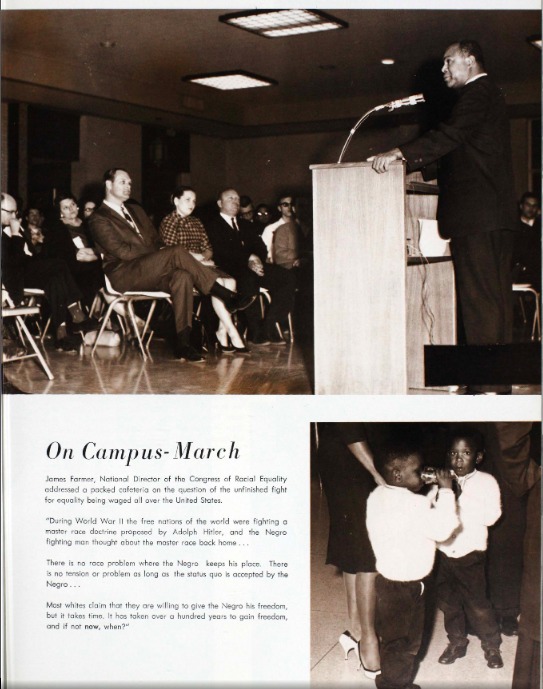

James Farmer, National Director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) visited the University in 1965 and spoke in a room packed with people regarding the fight for civil rights, coining the phrase “If not now, when?” [3] St. Edward’s University students were proactive in being inclusive and providing an environment where black people could be safe on campus during a period in which they were experiencing oppression around the country, which provided a space for the minority population to expand.

An article from the student newspaper, the Hilltopper Revisited, that describes the importance of the Negro experience on the country and advocates for their equal participation in society.

One student took to the newspaper to highlight the importance of the Negro experience on the United States and what they brought culturally to the U.S. According to the author without their experiences and their efforts, people would not benefit from many of the opportunities and economic gains that existed at the time. The student went on to advocate for an early affirmative action ideal, calling for inclusion of the minority populations in the workforce and giving them equal opportunity to succeed. [4]

The call for recognition provided an opportunity for members of the black community to come together and train themselves to be qualified in a society that was attempting to leave them behind.

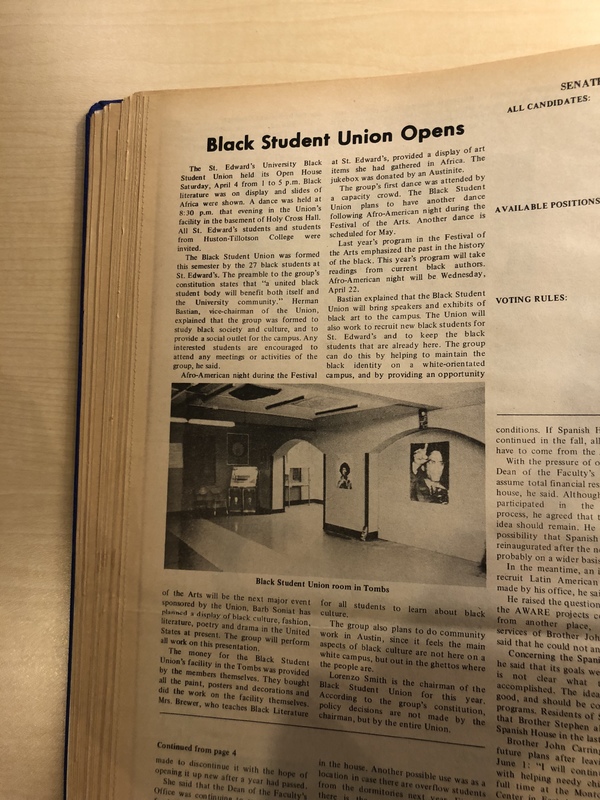

The black community at St. Edward’s University gathered together and took matters into their hands with the creation of the Black Student Union. The events hosted by the Union were paid in full by the members themselves.

The goal was to retain the black population already attending St. Edward’s University while simultaneously drawing more in.

They achieved this by hosting an art display including pieces from Africa and held themed dances that connected to their heritage and culture.[5] Due to their activism on campus the population became more diverse and doors of opportunity began to open for them.

The Black Student Union saw an empty space in which their culture was underepresented and they made their own pathway to achieve recognition.

A student article in the newspaper, the Hilltopper Revisited, that calls for the Chicano community to unite and make a stand for their community.

The Chicano Community at St. Edward's University

Arnold Elizalde was one student who took to the newspaper and called the Chicano students of St. Edward’s University to arms by stating that they needed to stand up for themselves and make the world they wanted rather than waiting for someone else to represent them. Members of their own community were encouraged to take action similar to the actions that were taken from other students of U.T.[6]

Eventually they succeeded and various programs were formed in order to unite the community. The Juarez-Lincoln center was formed on campus, which was a Mexican-American institution of higher learning that offered both bilingual and bicultural studies and promoted student diversity. This center was later moved off campus to become its own entity.[7]

The College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP) at St. Edward’s University was established in 1972 to serve the purpose of assisting migrant students through higher education. Students in the program received financial, moral, and academic support as they continued to pursue their baccalaureate, and this program still exists.

The Migrant Attrition Prevention Program (MAPP) and Educational Studies to Influence Migrant Advancement (ESTIMA) were also offered at St. Edward’s University for high school students that were the children of migrant farm workers. The program ran during the summer and students took school courses as well as performed part time work for wage in Austin.[8] These programs increased representation of the Mexican American community on St. Edward’s University campus as well as set them up to succeed throughout the duration of their lives.